|

Many anatomical features are used in the butterfly classification and a sound knowledge of them is essential for a correct identification of the species. During the metamorphosis major anatomical changes take place. Depending on the stage, its construction is well adapted to the challenges of life.

Adult (imago)

Like all insects, butterflies have a hard and strong external skeleton of chitin to support and protect the body.

It is important for the butterflies to maintain their water and ionic balance. The external skeleton also act as a barrier to microbes and chemicals.

The body of a butterfly consist of three parts: head, thorax and abdomen (Fig. 1)

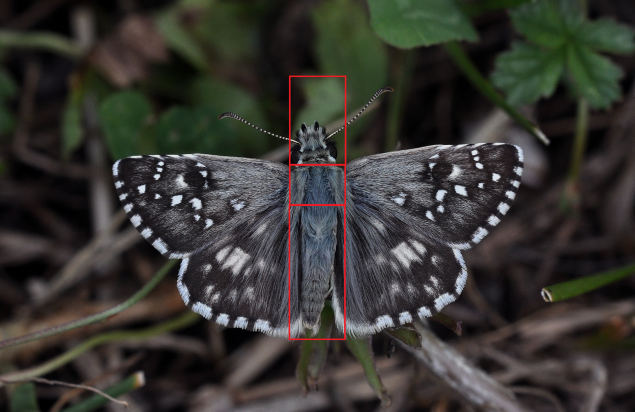

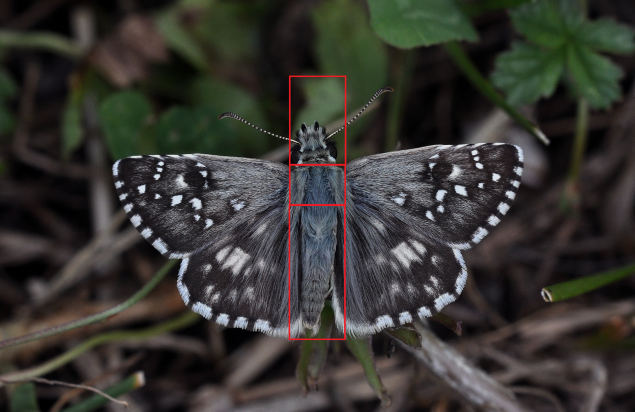

1. The body of a Pyrgus armoricanus, the head (upper part), thorax (middle part) and abdomen (lower part) Greece

Compound eyes, antennae, proboscis and palpi are located on the head (Fig. 2a-b). The head may be wide (Hesperiidae) or narrow (other families) relative to the width of the thorax. Compound eyes also have ultra-violet photoreceptors that help them to see flower patterns.

Butterfly eyes provide an almost 360° of vision with a similar accuracy. The front of the head between the eyes (frons) often bears a tuft of hair.

The proboscis is the feeding device of the butterfly. It consists of two parts and forms a tube through which water, moisture, nectar and minerals can be sucked up.

At rest, the proboscis is coiled (Fig. 2a). It can be unfolded for feeding (Fig 2b). The length of the proboscis determines the depth at which the flower's nectar can be reached.

The antennae are segmented and act as sensors. The antennae of the Papilionoidea have a clubbed tip (Fig. 2b). They help to locate a mate by detecting pheromones, to sense plants during feeding and ovipositing. Some species also use their antennae during courtship (e.g. Leptidea and Hipparchia). The antennae are wide apart in the Hesperiidae, close together in the other butterfly families.

The small palpi, below the eyes, are a pair of labia that protect the proboscis. They also have tactile and olfactory sensors.

2a. Head of a freshly emerged Aporia crataegi with he composed eyes, the coiled proboscis, the base of the segmented antennae and the palpi, Greece

2b. Head of a feeding Apatura iris with the unrolled proboscis, the palpi and the clubbed tip of the antenna, Romania

The thorax contains muscles, the wings (Fig. 3a-c) and also the legs are attached to it.

All butterflies have two pair of

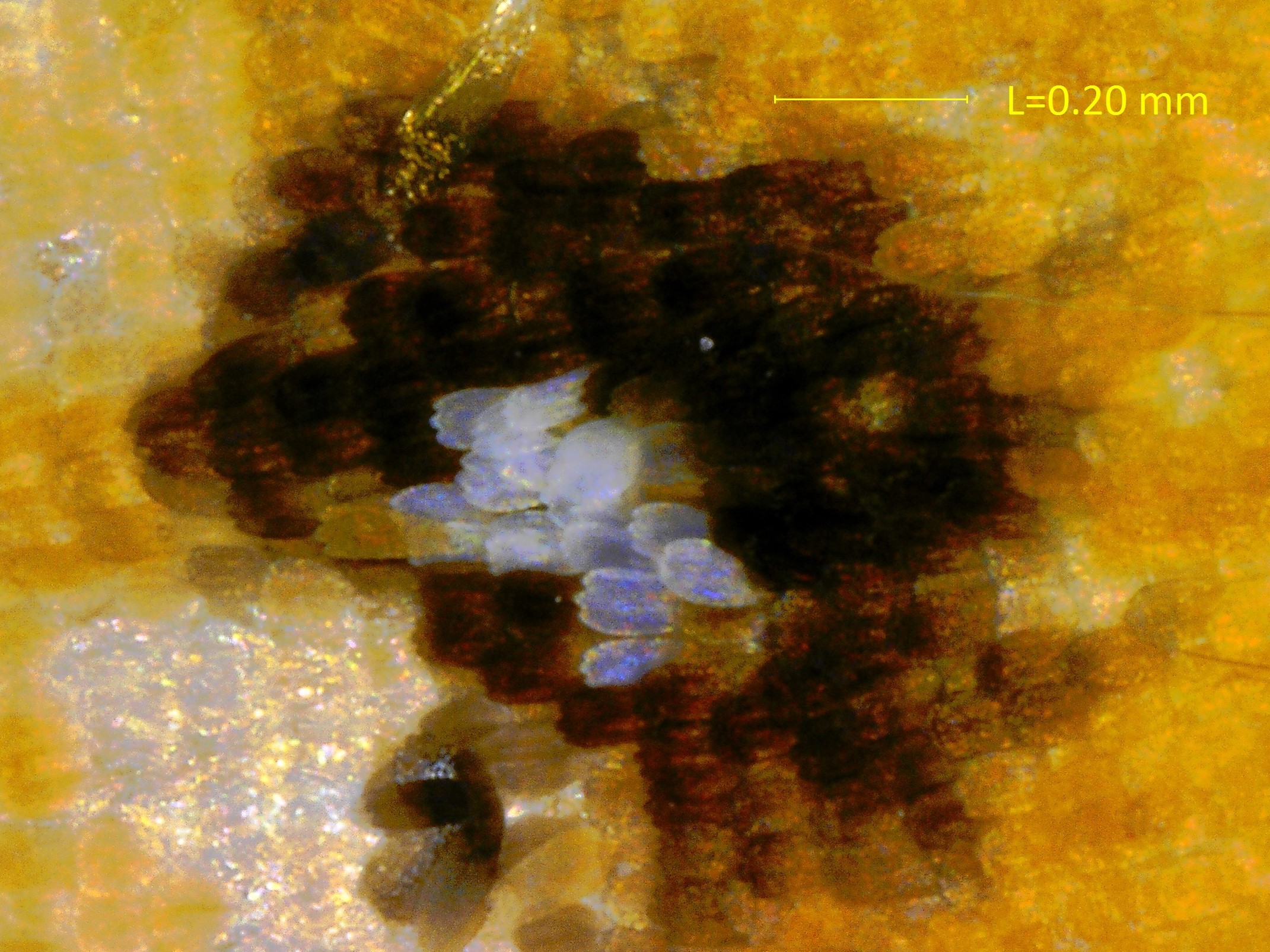

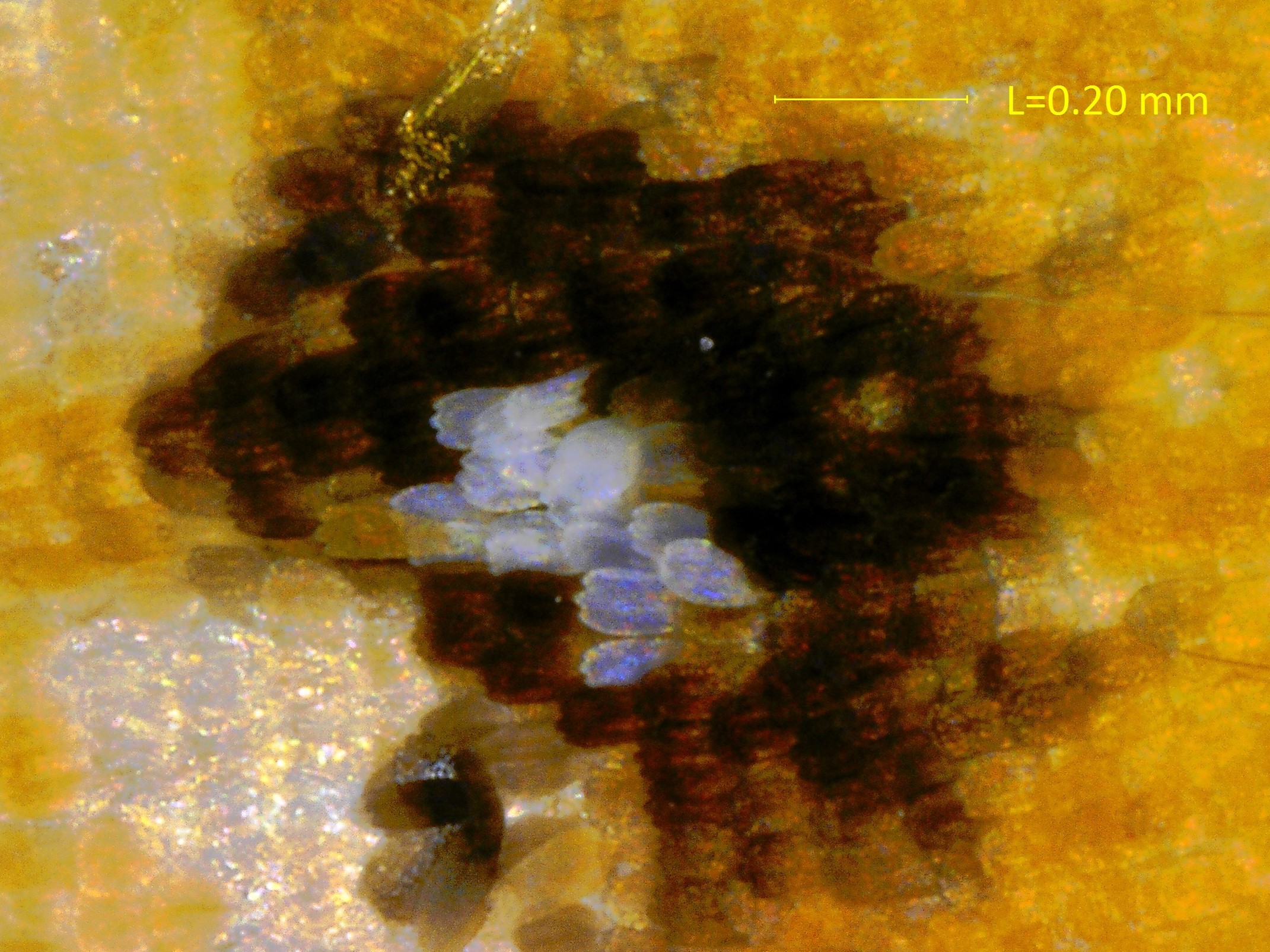

wings: the forewings and the hindwings. The scales (Fig. 5a) that cover them overlap like the tiles on a roof. They contain colored pigments that give color to the wings. Their arrangement forms the pattern of the markings. The scales of the Blues (Polyommatinae), Coppers (Lycaeninae) and Apatura break up the light to produce metallic colours.

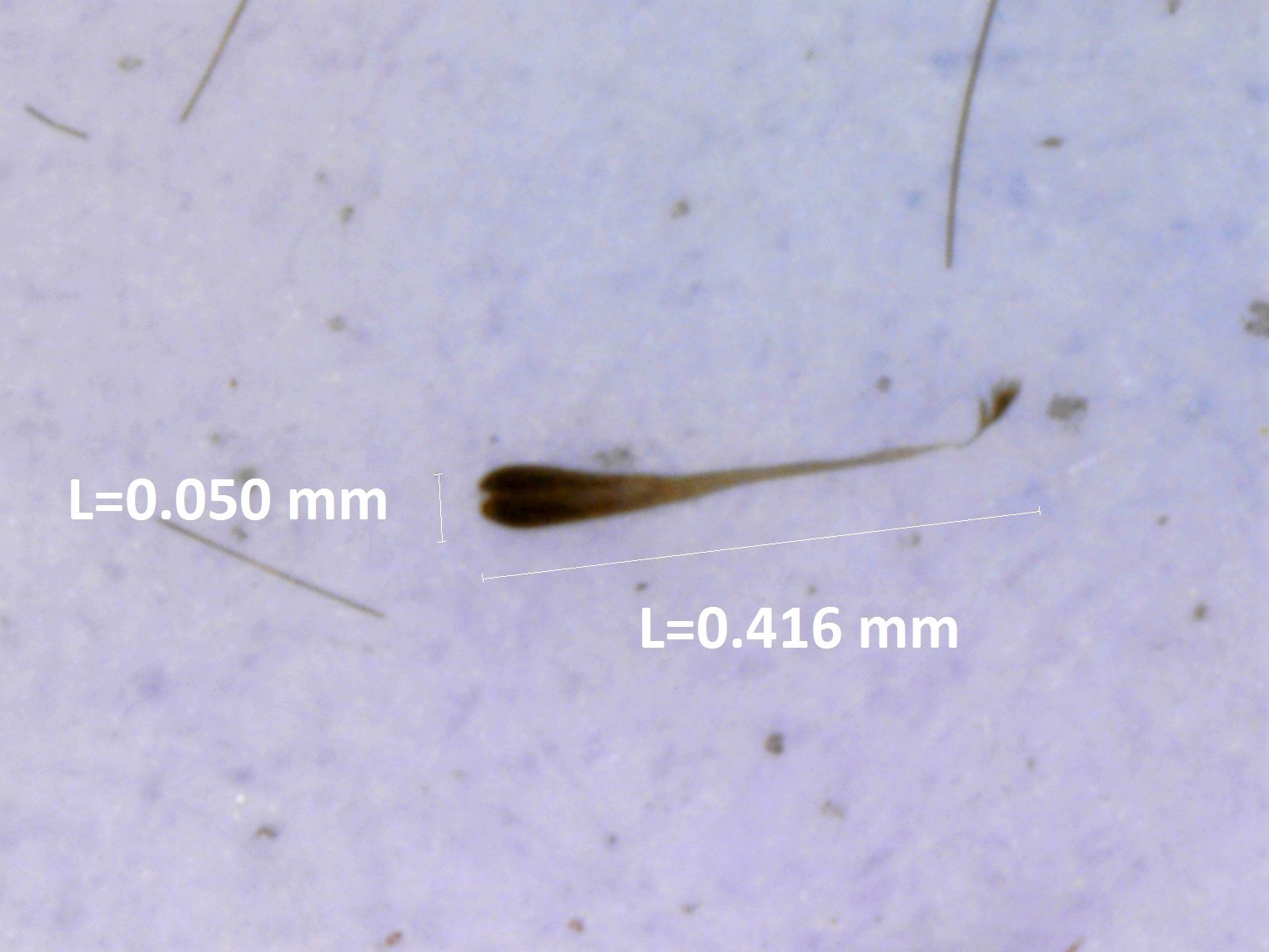

Scattered amongst the ordinary cells are other scales, the androconia, that are peculiar to males. They can also be useful for identifying similar species (Fig. 5b-c)

At the base of the androconia are gland cells that produce scents that attract females and/or play a role in the courthsip rituals. The androconia are often grouped together and form sex-brands.

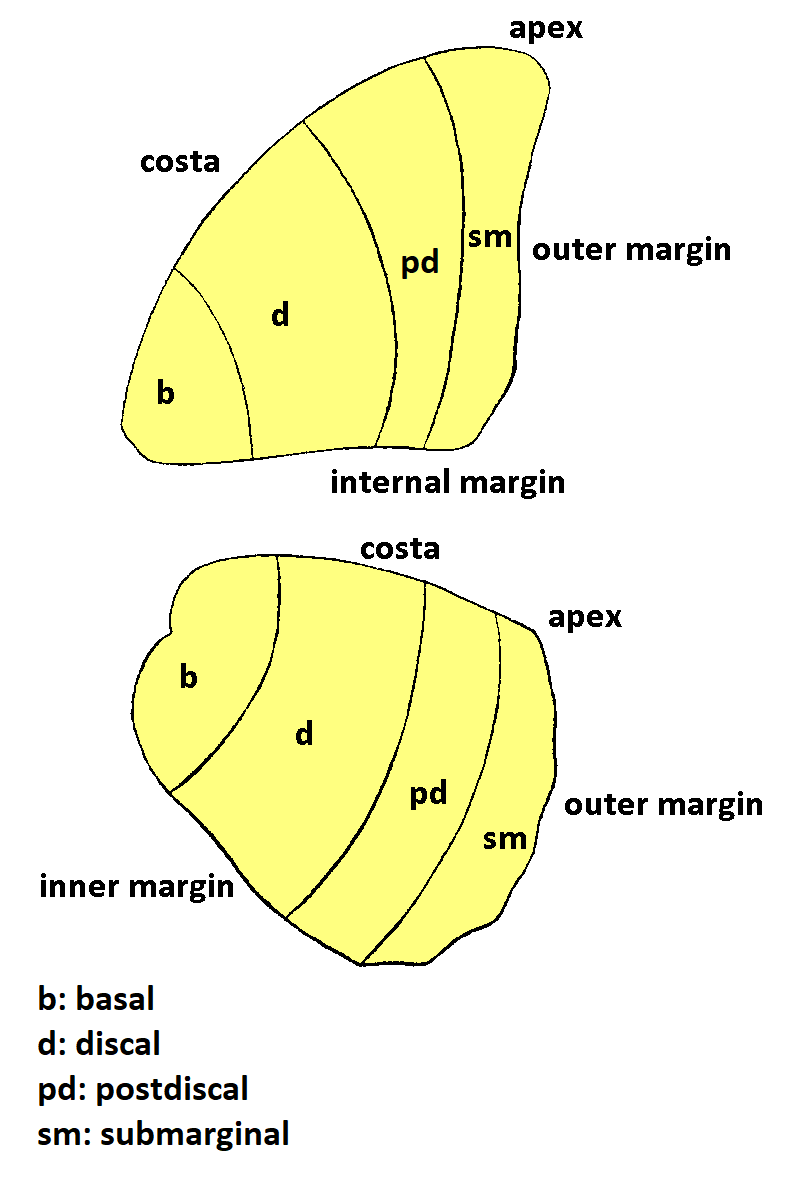

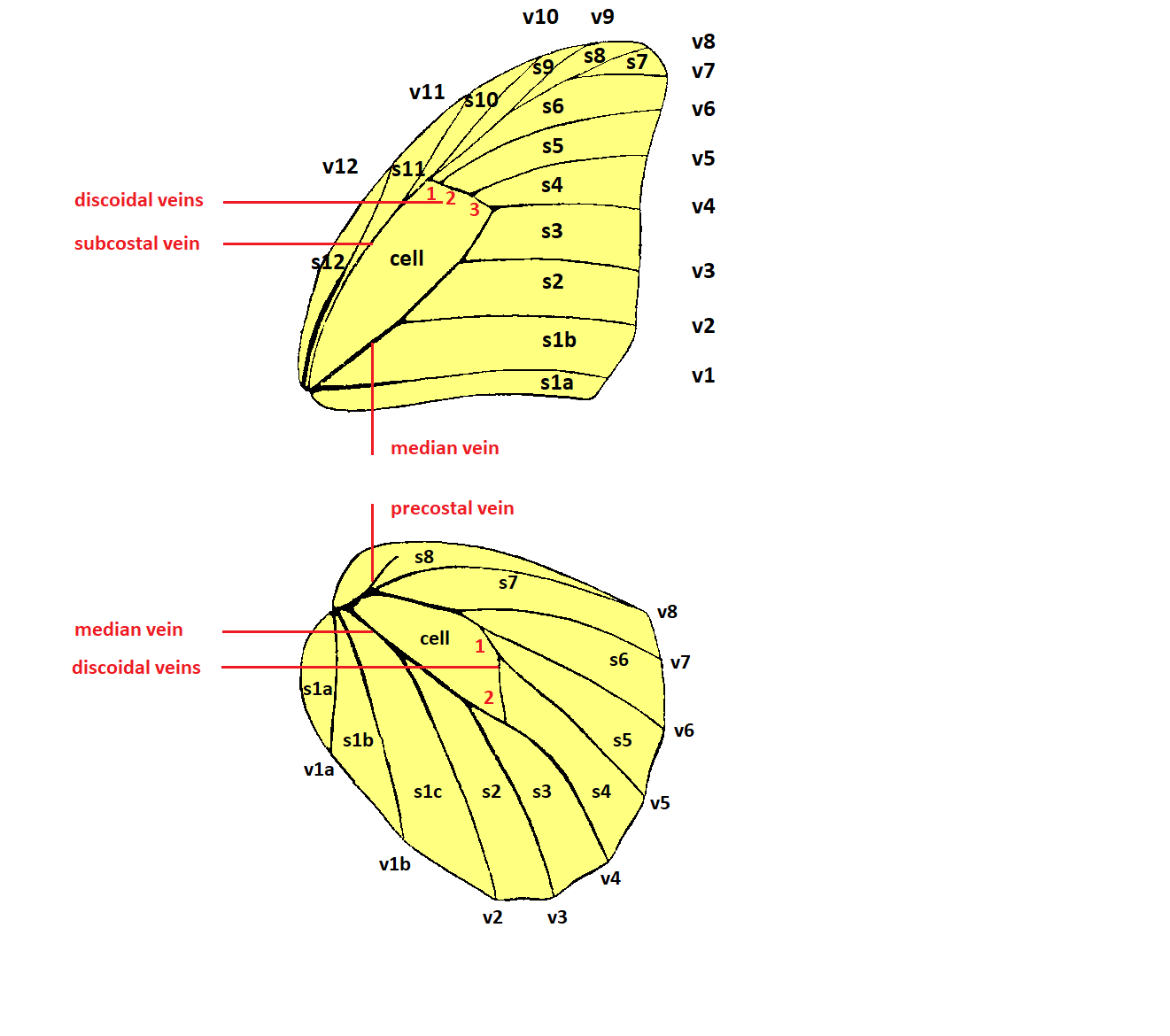

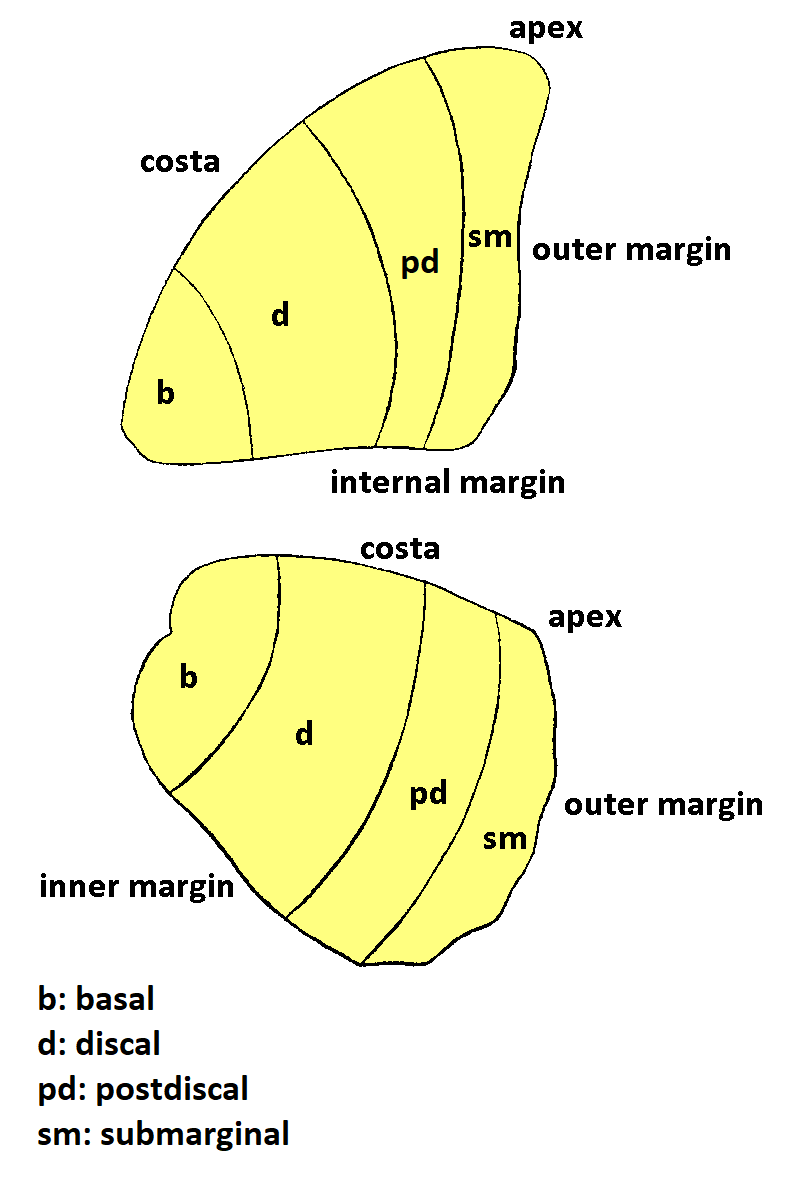

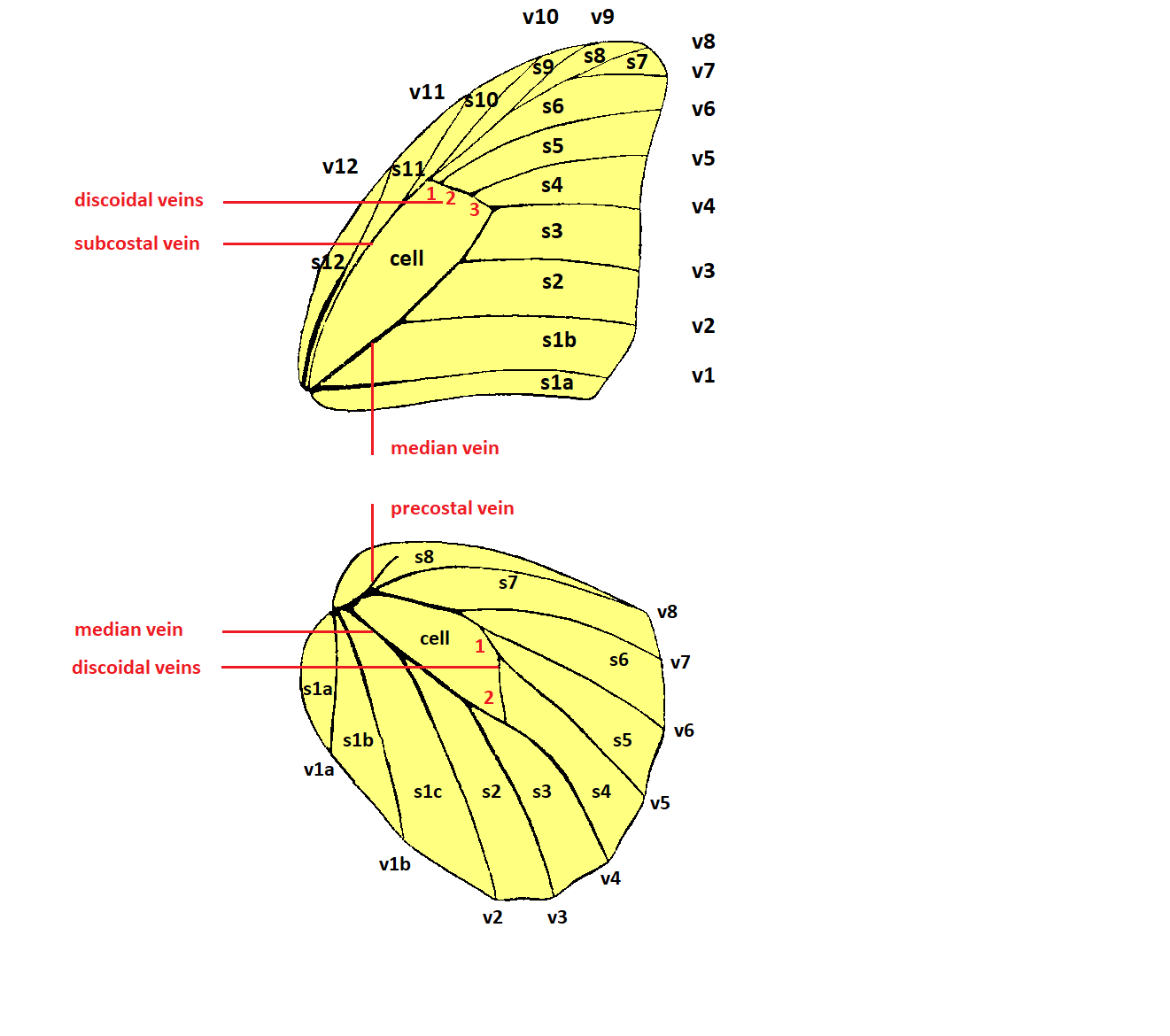

Solid veins provide a structural framework to keep the wing in shape. Vein structure is consistent among families, genera and species and is used in the classification. The veins are numbered, the spaces between the veins and the different areas of the wings have associated terminology shown in the schematic figures (Fig. 4a-b). We have adopted the simple system that Herrich-Schäffer introduced in 1844.

Insects typically have 6 legs (Fig. 2a) and this is also the case for butterflies. The legs consist of a basal hip-joint (coxa) and have three mobile segments: the femur, tibia and tarsus that usually ends with a claw. The tibia sometimes has one or more spines. They can be useful for the identification. The Nymphalidae family has only four fully developed legs (Fig. 3b-c) for standing. The two front legs are tiny, clawless and have little brushes that enhance the sense, smell and taste of the butterflies. They are folded against the thorax and are the reason for the common English name: brush-footed butterflies.

3a. Three pair of well developed legs of Polyommatus daphnis, Romania

3b. Two pair of well developed legs of Melitaea athalia, Albania

3c. Two pair of well developed legs of Fabriciana niobe, Albania

4a. Wing area notation ()

4b. Wing vein notation, the adopted system for naming: Herrich-Schäffer (1844)

5a. Scales in the hindwing ocellus of Pseudochazara amymone, Albania

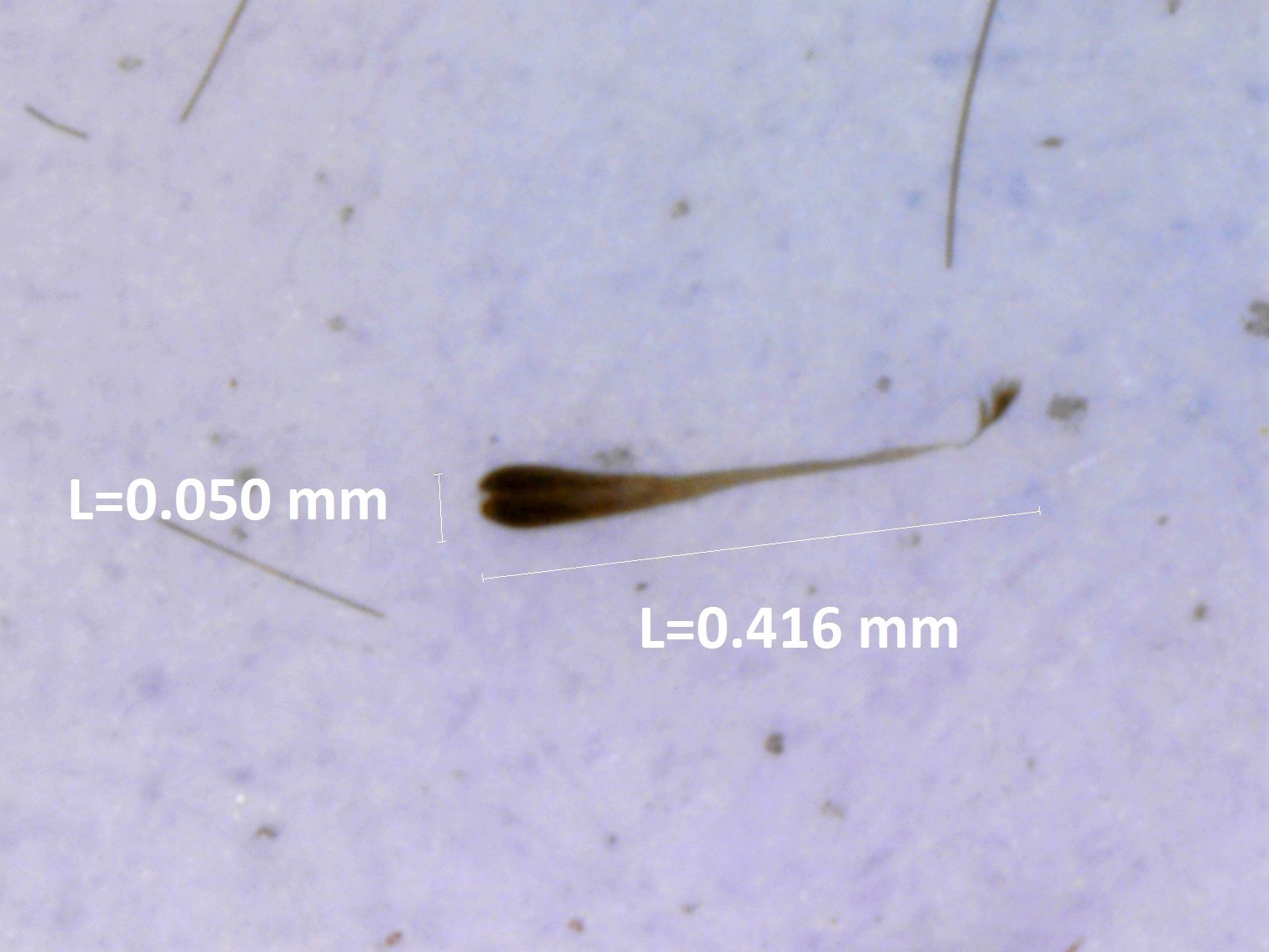

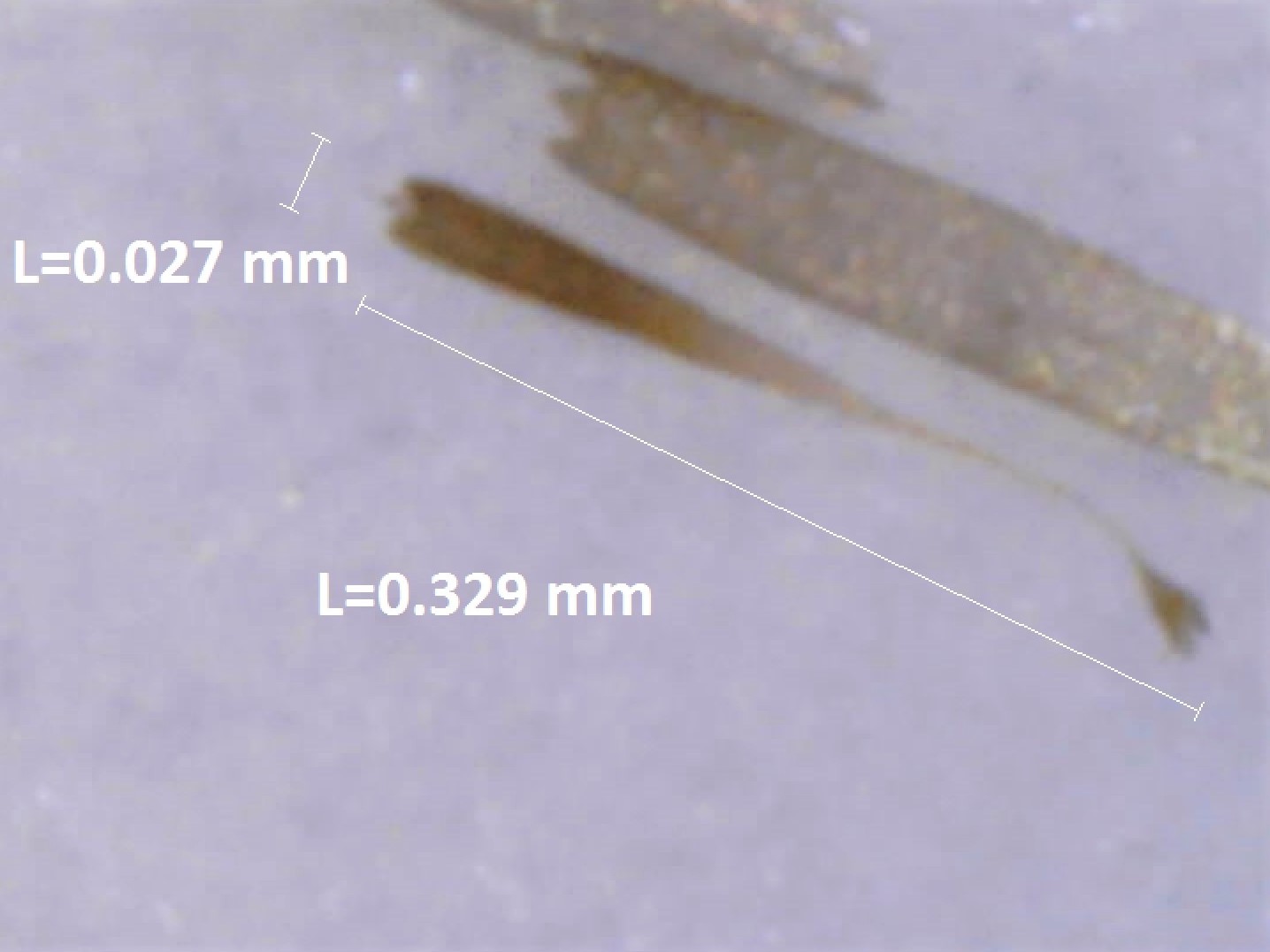

5b. Androconial scale of Pseudochazara amymone, Albania

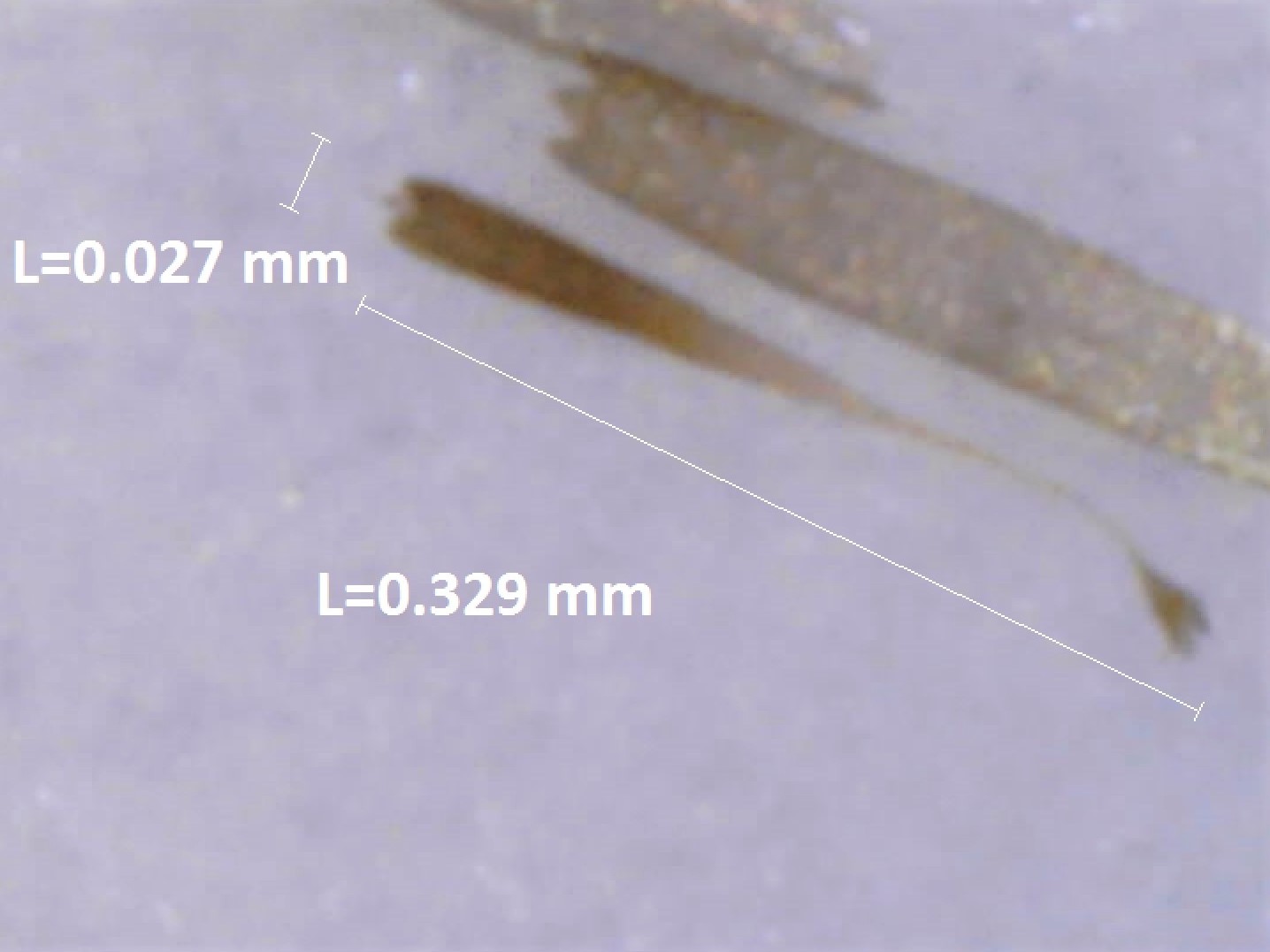

5c. Androconial scale of Pseudochazara tisiphone, Albania

The abdomen consists of ten segments that contain the digestive organs, the respiratory system and the reproductive organs.

The ten segments are connected by flexible tissue that allows the abdomen to bend during mating and egg laying (Fig. 6). In the segments are tiny holes, the spiracles that allow the butterfly to breathe.

6. Flexible abdomen of a ♂ Polyommatus ripartii. Distal parts of the male genitalia are visible. Greece (

The genitalia are located in the distal segments of the abdomen. In many cases the structures are unique to each species and these differences in the male and female genitalia often help to distinguish similar species and provide indications of species and group relationships for classification problems.

Male and female genitalia fit each other like a lock and key.

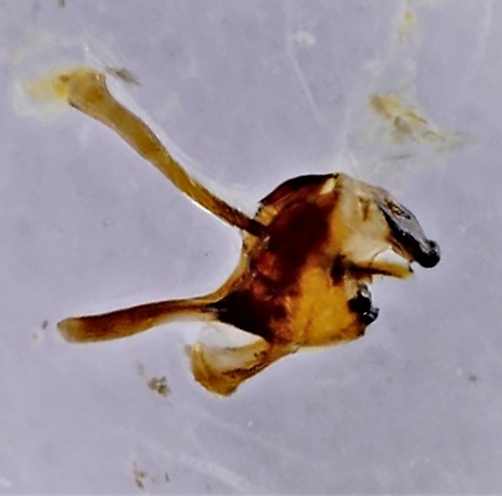

Males have a ring-like structure in the ninth segment, consisting of a dorsal tegumen and a ventral vinculum. A pair of valves (claspers) are atteched to it. The male has a middle organ (aegeagus or phallus) which extends to inseminate the female. Large parts of the male genitalia are highly chitinized and can be prepared quite easily.

Depending on the family and genus, these structures are very different. An important reference work for studying the male genitalia of European butterflies is the book by Higgins (1975).

For Leptidea sinapis / juvernica (Fig. 7a), Hipparchia semele / senthes / volgensis (Fig. 7b) etc. this is the basis for a correct identification because these species are visually indistinquishable from each other.

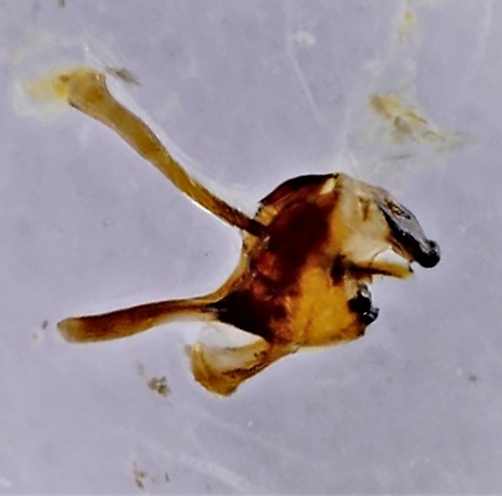

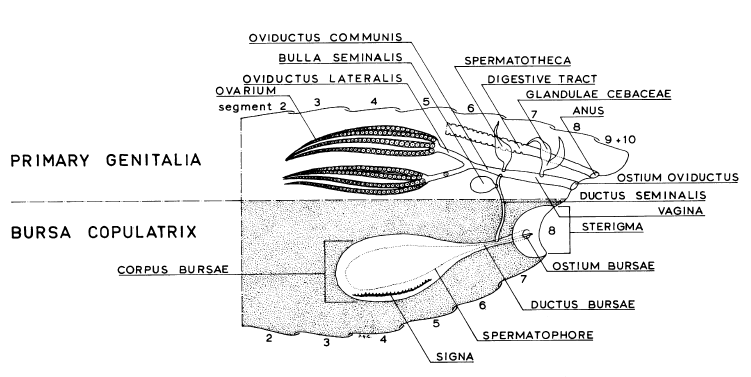

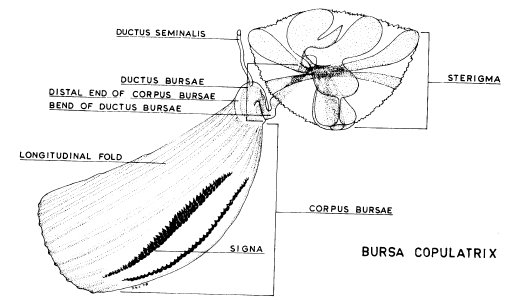

Female genitalia (Fig 7c-d) of butterflies consists of paired ovaries and accessory glands. A system of ducts and receptacles transport and store the sperm.

The female genitalia contain less chitin and are more delicate to prepare. This is probably the main reason why far less publications are available but they are useful for the related species mentioned earlier, as well as for Gegenes nostrodamus / Gegenes pumilio and Hipparchia fagi / syriaca.

7a. Male genitalia of Leptidea juvernica, Albania (

7b. Male genitalia of Hipparchia semele, Albania (

7c. Generalized genitalia of a female butterfly (

7d. Bursa copulatrix of a fagi-, or semele- group female butterfly (

Egg (ovum)

The egg (Fig 8a-b) is covered by a protective shell, called the chorion which has small grooves and ridges. The chorion is perforated by microscopis pores (aeropyles) allowing the respiratory exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

The micropyle (an opening near the end of the chorion) is an entrance for sperm, water and air.

Depending on the family, the shapes of the eggs (Fig 8a-b) are significantly different.

8a.

8b.

Caterpillar (larva)

The segmented body of a caterpillar consists of a head, a thorax and an abdomen. Basically, it is a tube for processing and storing food.

On the head (Fig. 9a) a caterpillar has powerful jaws. These well-developped mandibles have sharp cutting surfaces to cut leaves. Nearby are smaller parts, the two maxillae, which lead the food to the mouth and have taste cells. The tiny antennae provide sensory input relating to taste and smell. Caterpillars have 6 pairs of simple eyes. They are located on the sides of the caterpillar's head. The ocelli only detect light and cannot form an image.

Caterpillars have organs that produce silk, spinnerets. It is a tube-like structure on a larva's lower lip (labium) and can be used in various ways during pupation.

On the thorax are three pair of jointed legs (with hooks) and on the abdomen are pairs of stumpy prolegs (Fig. 9b) ending in small, hook-like suction cups (crochets) and on the last segment are the anal prolegs. Prolegs have no segments, they are no true legs. Although it doesn't look like it, a caterpillar is a six-legged animal.

On the thorax and the abdomen there are breathing pores (spiracles) and tiny hairs (setae). They are connected to nerve cells and provide information about touch in a relatively simple nervous system with a dorsal brain linked to a ventral nerve cord.

9a. Head of Pseudochazara amymone caterpillar in the first stage, Albania (

9b. Prolegs and anal proleg of Nymphalis xanthomelas, Sweden (SC,

Pupa (chrysalis)

Insect pupae are grouped into three categories based on physical appearance.

Lepidoptera have obtect pupae, a shell-like casing with the antennae, wings, legs tightly held against the body.

Depending on the family, the shapes of the pupae (Fig. 10a-c) are significantly different.

10a. Pupa of a Nymphalidae, Nymphalis xanthomelas, Sweden (

10b. (

10c. (

Useful link

(url) NC STATE Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Contact

|

xx

xx