|

10. Threats and Conservation

The reported decline from which it is not possible to recover?

The current global extinction, called the Anthropocene extinction, is a biodiversity crisis driven by worldwide human activities.

Scientists predict that at the current evolution of habitat loss and global warming, about 40% of all species will face extinction by the end of this century.

Main causes:

- Changes in land use (industrial agriculture for crops (Fig. 1a) and/or grazing of livestock (Fig. 1a-b), burning of fields (Fig. 1c), deforestation, afforestation, urbanization, abandonment, drainage, dams (Fig. 1d), quarrying, (Fig. 1e-f)… resulting in habitat loss, isolation, fragmentation and degradation.

- Pollution (greenhouse gases, nitrogen deposition, herbicides & pesticides, acid rain, …) affecting declining species inhabiting nutrient poor grasslands.

- Climate change influencing the life cycle of butterflies and plants, not always in a synchronous way.

In a recent study in Germany, with a standardized protocol to measure total insect biomass (deployed over 27 years in 63 nature protection areas) a dramatic invertebrate loss was documented and gave a clear picture of the status and trend of the local entomofauna in protected areas. This analysis estimated a seasonal decline of 76% and mid-summer decline of 82% in flying insect biomass over the 27 years of study (Hallmann 2017)

Butterflies are key indicators of environmental changes, reacting quick on such changes and one of the best studied invertebrate groups in Europe.

Different publications show important declining trends of butterflies in Europe.

In 1999 the status of European butterflies was published by the Council of Europe. Van Swaay et al. (2009) presented the methods and criteria used in the Red Data Book and assessed the status of the European butterflies. A decline in distribution was apparent for the 19 European endemic species making them an important conservation priority in Europe and nearly 40 species were considered near threatened and likely to move up to the category vulnerable if no actions were taken.

One of the objectives of this publication was to identify species of conservation concern in Europe.

Habitats with the largest numbers of SPEC 1-3 species (categories of species of European conservation concern) were different types of grasslands but also different types of woodland were important.

For Albania the number of SPEC 1-3 species given, is 14 or 8% of the estimated number of Albanian butterfly species at that time.

The estimation of the trend, estimated by Prof. Misja, was stable for all SPEC 1-3 species.

A selection of prime butterfly areas of Europe (PBA) was initiated (van Swaay & Warren 2003) for 34 target species (threatened or under EU

legislation)

Therefore it is less adequate for potential areas for threatened species endemic to the Mediterranean region.

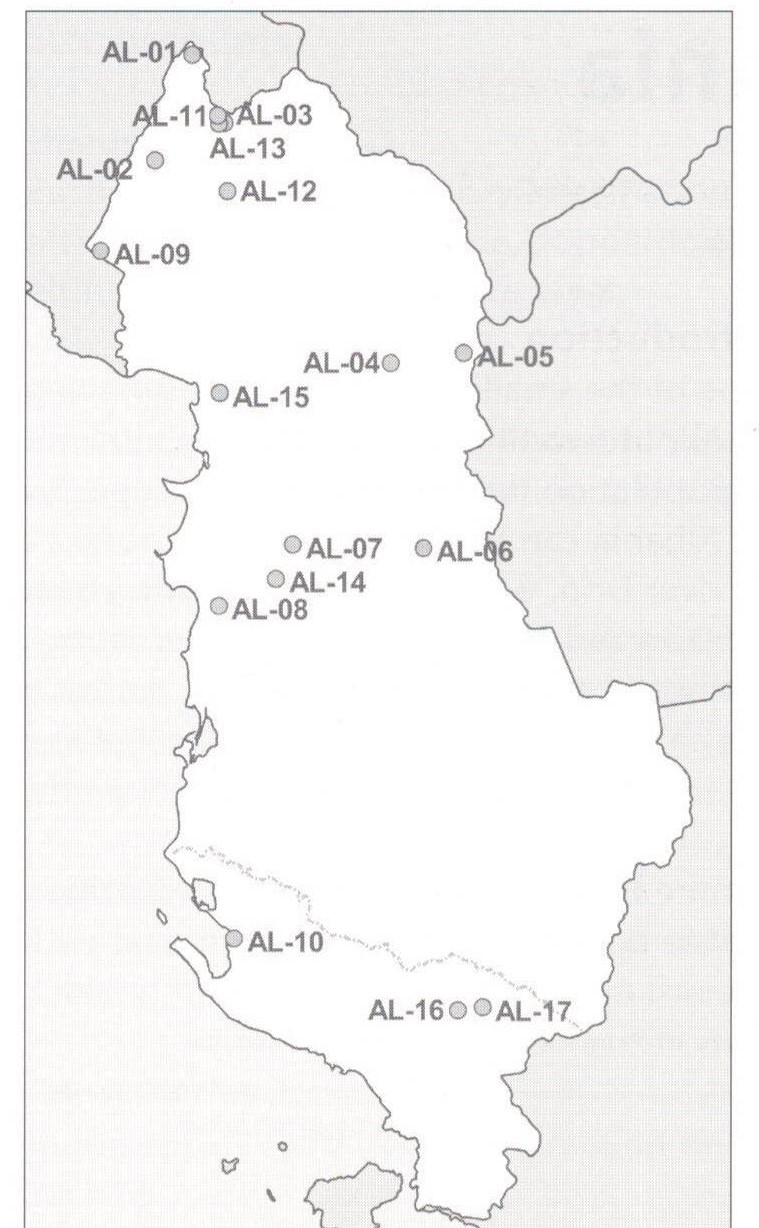

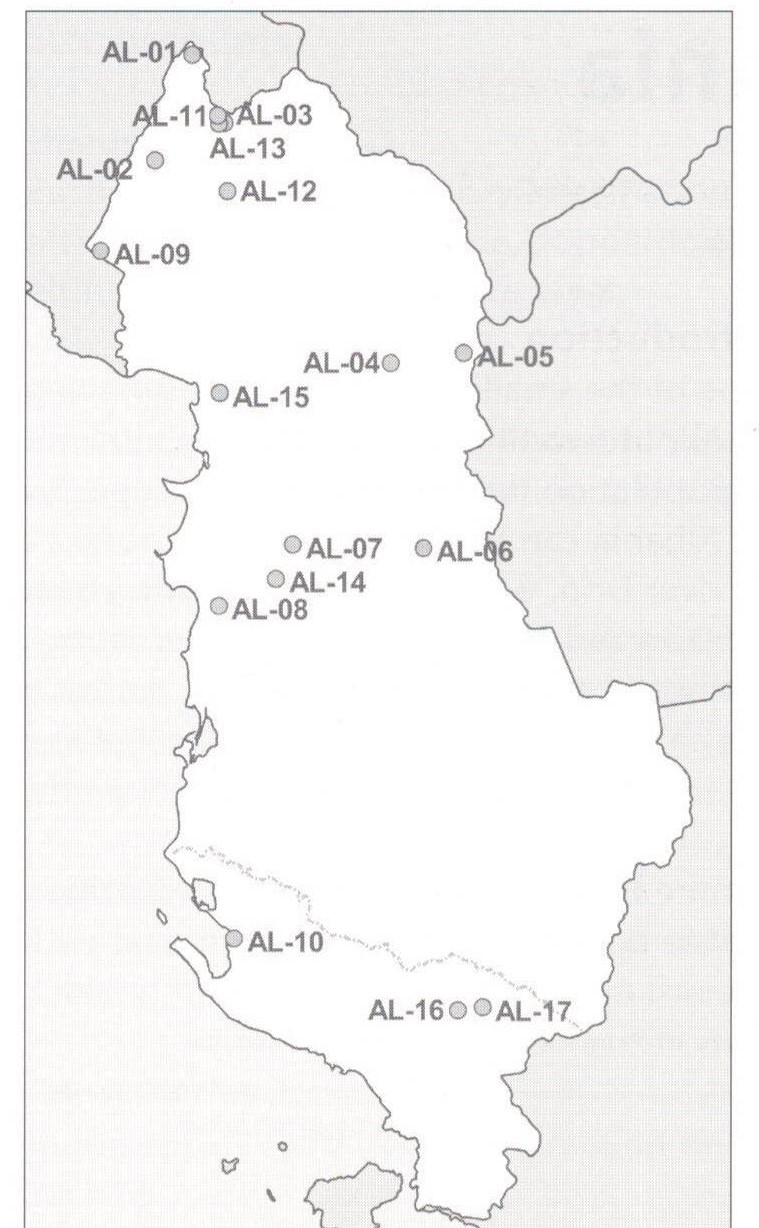

Prof. Misja contributed to the PBA project for Albania. Seventeen PBA (Fig. 2a) were identified, covering 34.504 ha and including 4 target species: Euphydryas aurinia, Lycaena ottomanus, Phengaris arion and Parnassius apollo. The main threats (Fig. 1a-c) for the target species in the 17 PBA were identified: abondonment, expansion of intensive agriculture, use of insecticides and herbicides, overgrazing of summer pastures in alpine and subalpine grasslands, afforestation and felling of woodland, uncontrolled fire, urban expansion and recreation/tourism.

In 2006, Prof. Misja included the Lepidoptera in the Albanian Red Book (Fig. 2b) and assigned a threat status to the selected species.

1a. Large cereal fields with grazing flocks of sheep in the plain near Korçë ()

1b. Overgrazing on fragile alpine grassland above 2000 m a.s.l. on Mali i Korabit ()

1c. Burning of fields. North of Përmet ()

1d. Fierza dam, Albania ()

1e. Quarrying. Burrel, Albania ()

1f. Quarrying. Vig, Albania ()

2a. Location of Prime Butterfly Areas in Albania.

2b. Cover of the Red List Book for Albania.

In 2010 a new Red List status of European butterflies was published. It was based on the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) Red List categories and criteria for Europe (larger than the EU). Despite the strengths of the IUCN Red list index, underrepresentation, misinterpretation and impediments for the effective protection of invertebrates have been reported (Cardoso et al. 2011).

Numa at al. (2016) assesses the conservation status at the level of the Mediterranean region using the IUCN Red List. The major threat cited in this publication is again habitat loss. The main conclusions are that there is a significant lack of information regarding distribution, population size and trends for the Mediterranean region, especially in the southern and eastern part of the region and that there is the need for an urgent conservational boost to halt the loss of biodiversity in the Mediterranean region.

The status of the species in the monographs, is based on this Red list.

The European Grassland Indicator (van Swaay et al. 2019) from 16 countries (no Balkan countries included) for 17 typical grassland species (15 species are resident in Albania) was updated and shows that the index of grassland butterfly abundance has declined by 39% since 1990.

Maes et al. (2019) compiled national species lists for 42 European countries and integrated national Red lists for 34 countries. This might be an additional tool to help prioritizing conservation actions for European butterflies.

Albania was included in this publication and recognized as a species-rich country but was not included in the integration of national Red Lists.

Warren et al. (2021) show extinctions of resident butterfly species at country level (United Kingdom, Belgium and the Netherlands) and strong decreases in overall numbers of butterflies based on distribution trends of long-running butterfly population data from standardized monitoring transects in these countries.

There are no objective data on the long term evolution of Albanian butterflies. Unlike western Europe, with a lot of volunteers and low numbers of species, in Albania the priority is doing more (observations) with less (people) to follow trends in the long term.

Standardised butterfly surveys can be done in transect counts (Pollard walks) or more extensive area-time counts and run on the long term.

As area-time counts are more suitable than transect counts to analyse temporal and spatial variability in butterfly occurence and can be used synergistically for the calculation of butterfly abundance trends (Barkmann et al. 2023), area-time counts look more appropriate to start monitoring the butterflies in Albania.

Prof. Anila Paparisto and Sylvain Cuvelier submitted a new Red List for Albanian butterflies.

In the new Red List 58 species are assessed, for some species adaptations are according to the recent research from field surveys.

A threat status is determined also for the newly discovered species.

In the monographs the recent Albanian Red List status is given.

Despite all the publications and legal instruments like CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora 1975), the Bern convention (Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural habitats 1979) and the EU Habitats Directive (Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora) the decline of the European butterflies is not halted, on the contrary.

Recently Engelhardt et al. (2023) quantified annual monitoring effect and used occupancy-detection models to compare species trends (Lepidoptera and Odonata) before and after implementation of the Habitat Directives. After implementation, monitoring efforts increased but did not prevent worsening of all annex species' occupancy trends and concluded that more serious broad-scale conservation measures are needed to halt biodiversity loss across Europe.

Moreover, the accession of new countries to the EU has large implications on their butterfly fauna as from the day they join the EU.

In each case, the same scenario repeats itself. It reduces the area with natural, semi-natural and extensively managed grasslands, brings important changes in forestry management etc.

This poses a serious threat as these countries, and it is also the case for a fast changing country like Albania, hold a disproportianely large number of threatened butterflies.

For effective protection of butterflies, habitat protection needs to happen both at a local level in individual sites and at a large landscape level.

It must go hand in hand with optimal habitat management. Butterflies, have complex habitat requirements, need food for adults and caterpillars in different niches of a habitat and different shelters depending on the stage. During centuries, butterflies relied on the tradional sytems of grazing, hay-cutting in grasslands, coppicing forests, etc. The continuation of such traditional regimes seems an utopy in Europe. Landscapes and sites change quickly to another management. It looks necessary to find feasible (read: economical) alternatives that will provide identical habitat conditions.

Recently Dapporto et al. (2022) published an atlas of mitochondrial genetic diversity for Western Palearctic butterflies and the data have a potential profound implication also for conservation. The atlas identifies intraspecific genetic variation (IGV) and maps important allopatric and parapatric lineages. It becomes possilbe to use a finer unit for conservation than the species unit. Small, isolated and genetically divergent populations can represent new candidates for conservation efforts.

Useful Links:

(url) van Swaay C. & Warren M. 1999. Red data book of European butterflies (Rhopalocera). Nature and Environment, No. 99, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg.

(url) van Swaay C., Maes D. & Warren M. 2009. Conservation status of European butterflies. — Ecology of Butterflies in Europe 21: 322-338. Cambridge University press.

(url) van Swaay C. et al. 2010. European Red List of Butteflies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

(url) Cardoso et al. 2011. The seven impediments in invertebrate conservation and how to overcome them. — Biological Conservation 144: 2647-2655.

(url) Numa C. et al. 2016. The status and distribution of Mediterranean butterflies. IUCN. Malaga, Spain.

(url) Hallman C., Sorg M., Jongejans E., Siepel H., Hofland N., Schwan H. et al. 2017. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. — Plos One 12(10) e0185809.

(url) van Swaay C. et al. 2019. The EU butterfly indicator for grassland species: 1990-2017: technical report. Butterfly Conservation Europe & ABLE/eBMS (www.butterfly-monitoring.net)

(url) Maes et al. 2019. Integrating national Red Lists for prioritising conservation actions for European butterflies. — Journal of Insect conservation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-019-00127-z

(url) Warren et al. 2021. The decline fo butterflies in Europe: Problems, significance, and possible solutions. — PNAS 118(2) e2002551117. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002551117

(url) Barkmann F., Huemer P., Tappeiner U., Tasser E. & Rüdisser J. 2023. Standardized butterfly surveys: comparing transect counts and area-time counts in insect monitoring. — Biodiversity and Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02534-2

(publication and atlas) Dapporto et al. 2022. The Atlas of mitochondrial diversity of Western Palearctic butterflies. — Global Ecology and Biogeography. 00, 1–7.

(url) European Butterfly Monitoring Scheme (eBMS) website.

(url) eBMS - mobile application.

(url) Engelhardt E., Bowler D. & Hof C. 2023. European Habitat Directive has fostered monitoring but not prevented species declines. — Conservation Letters 16 e12948.

Contact

|

xx

xx